The actual work flow didn't go this way, but for the sake of clarity (Of course clarity is a relative term!!) I've broken down constructing the jewelry box for sister L to give to sister G into it's main components.

This post will deal with the trays themselves.

But first, this was the starting point for the actual cutting and fitting part of the project. Over on the left are a couple chunks of Black Walnut. There in the middle are some boards of Tiger Maple. I bought these sight-unseen as Birdseye Maple but actually like the Tiger Maple I ended up with better. And over there on the right is a $200 chunk of 8/4 Teak.

All of the above has been on the rack in my shop for years, being slowly nibbled away at as I build various projects.

Not shown is a bit of left over hardboard (Masonite) that I cut the bottoms of the trays out of and, because it would have been a bit cumbersome to carry into the shop and hoist up onto the table saw, the 50 foot Redheart Cedar tree that gave up a few fire-wood sized blanks that I turned into a whole lot of shavings at the lathe in the process of producing a few rails for the small trays.

The tree had succumbed to beetles after being weakened by our multi-year drought. Then when the rains did return this spring the dead tree didn't have enough hold on the ground to stay up on its feet any longer.

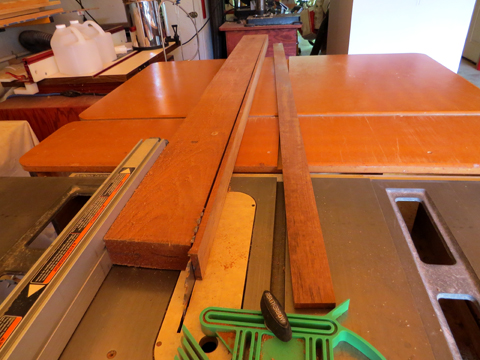

First step to building the trays was to rip a couple slices off the Teak slab that would eventually become the tray sides. That chunk of Teak is heavy and when taking off thin slices like this I prefer to keep them on the free side of the blade rather than risk having them trapped between the blade and the fence. This takes a little more setup in order to get each slice about the same thickness because I have to adjust the fence for each cut and that's more art than science, but I would be running the slices through the planer anyway to clean up saw marks and save myself some sanding, and while I was doing that the planer would also trim them up to the same thickness.

At this point I hadn't yet discovered that I would be building a second small tray so I had to come back later and do this all over again to get one more slice. . . .

Since the stacked trays had to fit within the depths of a 3.5" drawer I couldn't use the entire 2" width of the slices I just produced so I trimmed a little off the slice that would become the bottom tray, (But not enough as it turned out!) and a wider bit off the slice that would become the shallower upper tray.

With the tray sides now the right height I installed a flat-kerf blade in my table saw. As you might have already figured out, this is a blade designed to leave a flat bottomed cut rather than the more usual M shaped bottom normal crosscut and ripping blades would leave. It's a little detail that will never be seen but - well - might as well do it right, or at least try once in a while. . .

After a little bit of careful setup (And a slight detour as I fished one of my brass setup bars from the bowels of the table saw.) I cut the dadoes that would ultimately hold the hardboard tray bottoms.

Next step was to rough-cut the sides of the trays out of the long pieces I had been working with, making absolutely sure to cut them a little long. Then I tilted the blade to 45 degrees and carefully trimmed them to final length while mitering them at the same time.

In the setup above I've mitered one end of all four pieces that make up the ends the bottom tray and the long sides of the upper tray, all of which are the same length. Using my speed square (With a brass setup bar holding the far end up so the pointy ends of the 45 degree miter cuts would butt flush against the square) up against my highly accurate Osbourn miter gauge, I lined up all four pieces before running them through the saw one last time.

This ensured they all came out square (In a mitered kind of way.) and the same length, both of which are pretty important when you're trying to end up with a square box. In fact having all the same length is more important than their actual length. I did this two more times to get the ends of the small tray and the sides of the lower tray cut to equal lengths as well.

At this point I was still working under the delusion that I was only building one small tray, so later I had to do all of this all over again to produce the second small tray. . .

The photo above shows all four sides of the first small tray, milled, dado-ed, and mitered. Laying on top of them is a thin slice from the glue-up I did to create the rails for the bottom tray. (That's another post yet to come.) And there in the top center of the photo, my dado stack set up so I can inlay the walnut/maple glue-up into the tray sides.

It wasn't until I had this thin piece of the walnut/maple glue-up laying

on the table saw, a scrap bit of off-cut at this point, that the 40

watt bulb in my head finally warmed up enough for me to notice. 'Hey! this would make a cool looking

inlay around the outside of the small tray!'

Now believe me, this would have been a whole lot simpler if I had just planned on doing the inlay from the start, but my projects often evolve along the way so this wasn't the first time I've ended up doing things backwards.

Once the inlay dado was cut and the strips carefully edge-sanded until they fit snug, I glued everything in place, stacking the glue-ups together with waxed paper keeping parts that weren't supposed to stick together from sticking together. This way I could put clamp pressure on all the glue-joints with just four of my Bessey clamps.

These are great clamps that apply a nice even, parallel pressure across a wide area, but they are expensive so my supply is limited.

I cut the depth of the dado so the the inlay would sit slightly proud of the tray sides when glued in place. That way they could later be sanded down flush and ensure a clean, tight look.

Here I've got one of the tray sides clamped in the bench vice and rough sanded down flush, with another side next to it waiting for the same treatment.

After rough sanding with 100 grit in a small belt sander to quickly remove the bulk of the excess, I hand sanded down through the grits, 150, 220, 320 until I reached 400. This leaves a velvety smooth surface that will take a clear finish nicely.

But I should point out that I don't get obsessive about the sanding, nor do I fall apart over the occasional less than perfect fit and finish. I think a hand built piece is enhanced by having a few flaws left over from the process. If you must have cookie cutter perfection then go to Walmart and buy mass produced plastic instead.

The biggest problem with doing the inlay backwards like this was that I now needed to go back and trim the inlay flush with the finished miters I had already done. This requires a lot of very careful and painstaking work since the last thing I wanted to do was accidentally cut too much off one end of one of the pieces! That would mean the tray wouldn't fit together square anymore and - well - it's kind of important that they fit square!!

I very carefully lined thing up by eye and cut close while not overcutting, then took advantage of the fact that the carbide teeth on the saw blade stand slightly proud of the steel body of the blade.

By carefully butting the cut face up to the steel of the blade, holding everything tightly in place, then running that setup through the spinning teeth, I could shave very thin slices off the inlay until I got it down flush with the miter cuts. This takes a lot of time since the blade must be stopped and restarted for every pass and the setup must be done carefully, but - well - it was my own fault I was in this fix. . .

This is a closeup of the finished result. And I only had to do it all over again seven more times!! Note to self, it sure is easier if you do things in the right order in the first place!

Here you can also see the radius I sanded into the top of the tray sides while doing the hand sanding a couple steps ago. A hand built piece should invite handling and nothing disturbs the tactile experience like unnaturally sharp edges.

Speaking of tactile, when building boxes it's important to sand the inside before assembly as it's nearly impossible to try do it once the parts are assembled and you have to work against inside corners.

But once again, I was working ahead of myself.

Once I got the lower tray assembled I decided the whole thing was just a little too deep, so I ended up cutting about 5/16th off the top all the way around. Of course this included the radius I had so painstakingly put on, so I had to hand sand that back in all the way around. . .

Since the tray was already assembled at this point that meant I had to deal with getting a decent looking radius at the inside of the four corners as well as along the edges. I did this by wrapping sand paper around the handle of a small paintbrush and carefully shaping the corners, down through all 5 different grits of sandpaper!

Sanding is rarely the most sought after job in the woodshop, but if there was any bright spot to this at all, it's that the oily Teak produces a heavy sanding dust that simply lays down instead of floating around everywhere.

But still, note to self; stop doing things backwards or I'm going to have to dope-slap you!!!!

In the photo above I'm setting up to glue up one of the trays. The tray bottom, sitting top right, has been cut to size so it fits into the assembled sides with just a little extra room left over to account for wood-movement over time. It won't generally be seen, but I went ahead and pre-painted the underside of the bottom black anyway because you never know.

The sides are laid out there on the lower right and I've already done a dry run to get my strap clamp set up and ready to go.

If you're going to make more than a few small boxes a strap clamp like this sure does make things easier. It's a bit finicky to get all the bits where they need to be, but once that's done it can be gently snugged up to hold everything in place while you make last minute adjustments, then quickly and cleanly applies even pressure all the way around with a couple twists of the red handle that's just barely visible on the left.

Teak is an oily wood, so before any glue goes on I wipe the gluing surfaces down well with acetone. This temporarily clears some of the oil out of the way and allows the glue to get a decent grip on the wood fibers. The oil will soon migrate back but by then the deed is done.

Once I have the oils cleaned up a little so the tape sticks better, I carefully mask the inside corners before reaching for the glue bottle in case there's any squeeze-out once I clamp things up.

Squeeze-out is easy to clean up on the outside but a real bitch on the inside!

By carefully timing it right, I can remove the tape, and any squeeze-out right along with it, just at the point where the glue is hard enough to stay put but soft enough to remove cleanly. This takes patience because if you do it too soon you end up with a mess anyway, yet if you get distracted and put it off too long the glue has hardened to the point where it will take a lot of careful work with a fresh #11 blade to get it all cleaned up without damaging anything.

I tend to leave glue-ups clamped overnight. This is longer than most modern adhesives need but at this stage I prefer to play it safe.

Once the clamp came off a final round of sanding on the outside cleans things up and eases the sharp corners.

Just because the trays are now assembled doesn't mean I'm done though.

Next time, the process of gluing up the blank from which I then cut the rails for the bottom tray (And the inlay for the small trays.)

No comments:

Post a Comment