Unless I had some way to separate all the various bits of - well - jewelry; some dividers of some sort; then the lower tray I had built would not really be anything more than an inverted shoebox top! Little more than a junk drawer. A fancy Teak junk drawer but still, just a junk drawer.

To come up with some dividers to install into the lower tray that were more interesting than - well - a few sticks, I wanted to create a glue-up of alternating Maple and Walnut.

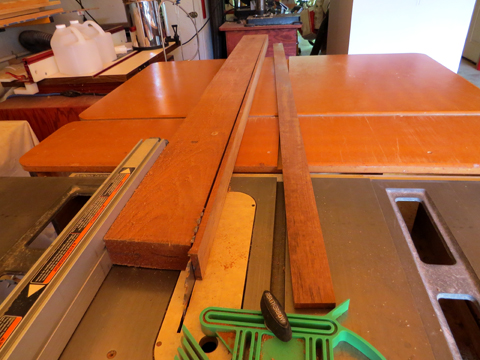

I started by turning my boards, Walnut on the left, Maple on the right, into small strips at my table saw. Unlike when cutting the strips for the tray sides out of the Teak slabs, this time I didn't care if each strip was the same width or not. In fact I went out of my way to make sure the strip widths were more or less random.

With the boards turned into strips I then stacked those strips, alternating a Maple then a Walnut then a Maple and so on, taking care to select stick widths randomly.

If I would have just settled for dividers with perpendicular laminations, then at this point I could have just glued everything together and been done with it, but I wanted the laminations to run at an angle to create more interest.

An admirable thought perhaps, but it created a whole lot of extra steps!!

First I had to turn my long sticks into lots of shorter sticks. There actually was some science to selecting the length of these sticks. It was ultimately dictated by the final angle of laminations and the width of my surface planer but I won't go into the specifics now since it's much easier to see what that's all about later.

Then I divided those stacks of short sticks into even smaller stacks of about 8 sticks each. It was very important to ensure that each small stack consisted of an even number of sticks so that when the the stacks were joined back together again the alternating pattern of Walnut - Maple - Walnut would remain intact.

Glue was then applied to one side of 7 of the sticks. If glue was applied to the eighth stick it would try it's damndest to glue itself to the clamp and - well - having been-there-done-that before, believe me, it's a less than desirable outcome. . .

Some time back one of the wood magazines ran a test on gluing methods. One method, and clearly the simplest, was to just lay a bead of glue down and then let the pressure of clamping the joint spread the glue. A second was to evenly spread the glue across both gluing surfaces then clamp. And the third was to evenly spread glue across one of the surfaces and clamp.

The results clearly showed that the bead and clamp method was not as strong as the spread and clamp. (The test being that the wood fibers break before the glue joint fails.) The tests also showed that spreading glue on one surface then clamping consistently produced a joint at least as strong as spreading it across two surfaces before clamping. The exception would be very porous woods that tend to wick moisture deep into their fibers, such as the well cooked and tortured surfaces of most plywoods or very oily woods where glue needs to be massaged into the fibers of both surfaces before clamping, such as Teak. In those cases spreading glue on both surfaces first produced a better joint. Since I was working with glue-friendly hardwoods the one-surface method was just fine.

There's all kinds of glue applicators out there designed to make this job easier and I've owned several of them at one time or another, but I find the quickest, neatest and most accurate way to spread glue is with my finger. I lay a bead of glue down the surface then evenly spread it with my finger, making sure I get complete coverage.

Once the glue was spread I reassembled the sticks into a stack and then clamped them up. I applied three of my Bessey clamps to each stack which ensured even pressure across the full length of the relatively thin and flexible sticks.

As I added clamps I snugged each up gently then pushed everything tight against the relatively flat surface of my workbench to get as flat a glue-up as possible. (I wasn't going for perfect which is good because I don't care how much effort you put into it, there is no such thing as a perfect stack glue-up!) I also kept an eye on the ends of the sticks to make sure they lined up reasonably well, though that was not terribly critical since the ends would be cut off and discarded later in the process.

Once I had everything generally in place I carefully tightened the clamps bit by bit to their final pressure, which isn't he-man-gorilla tight since that tends to squeeze so much of the glue out you end up with a dry joint, which is a weak joint.

Depending on the type of joint, I shoot for snugging the clamps up firmly then give them another quarter to half turn. The trick here is to get a sufficiently tight fit between the surfaces for a strong glue line then hold everything in place until the glue has a chance to set. You're not trying to squeeze the sap out of the wood like it was a sponge!

I set each of my glued-up stacks aside overnight to make sure they were well cured before the next step.

Because of my limited number of Bessey clamps it took two days to glue up all eight of these small stacks.

At this point there was a lot of glue squeeze-out, which isn't necessarily a bad thing. If you don't see at least some squeeze-out then the joint is potentially dry and could be weak.

The surface of the stack is far from perfectly even, especially the surface that was on top during the clamping phase since my Walnut board was slightly thicker than the Maple to start with, but not to worry, that will be dealt with soon.

The next step is to knock some of that excess glue off with a scraper. I've tried a lot of different ways to do this and for me the one that seems to work best most of the time is using a hand scraper with a replaceable carbide edge.The replacement edges are not that expensive and glue, especially glue blobs, can be hard on sharp tools, so getting rid of what you can before subjecting your expensive blades to it is a good idea.

With the worst of the excess glue removed I moved over to the jointer. I have an 8 inch jointer which was one factor dictating the maximum width of my initial stacks.

A quick pass or two of what was the bottom side of each stack during clamping, the most even side, through the jointer evened everything up and left me with nice predicable surfaces for the next step.

I left the other side of the stacks rough because it will be a couple more steps before I'm ready to worry about them.

I decided to take the easy way out and go for laminations set at 45 degrees. This way I could turn the resulting dividers end for end all I wanted without screwing up the pattern.

I used my speed-square to get me in the ballpark. It was also important at this point to ensure that ultimately I would be dealing with a 12" to 13" wide final glue-up since I have a 13" planer that the whole thing would have to fit through at some point.

Then I marked the 'ends' to make sure I could get everything back where it needed to be, (If you look close you can see the pencil ticks near the left side of the two closest stacks.) as well as give me a guide when I was spreading the glue. It was very important that I keep the smooth side down against the bench at this stage and I also had to guard against flipping any of the stacks end for end or I would have ended up with Maple - Maple or Walnut - Walnut sticks adjacent to each other at the new glue line.

Just like when I glued the sticks into stacks, I then glued the small stacks into larger stacks, but only a maximum of three per glue-up to ensure I could keep control and get good alignment and clamping pressure.

At this point I didn't have to be quite as close with the clamp spacing since the glued up stacks are much stiffer, I mean

way stiffer, than the original sticks, so clamping pressure would be distributed over a wider area. (It's the difference between pushing down in the middle of a pillow or the middle of a board. The floppy pillow won't transfer any of the pressure out to the ends but the stiffer board will.)

This turned my 8 initial stacks into 3, 2 of three stacks each and 1 of two stacks. (OK, if you stuck with me on that you're doing well. I had to proof that sentence several times to make sure I got it right!)

Again, I left the glue-ups to cure overnight.

You can also see that by now I was getting better at judging just how much glue these particular joints needed so there was much less squeeze-out. Just enough that I knew the joint wasn't dry.

But I wasn't done yet! The next morning I took my two new three piece stacks and glued them up into an even larger, 6 piece stack, taking great care to maintain the offset that would result in the 45 degree laminations I wanted.

Because of curing time I had to wait until the next morning to glue on the final stack required to create the ultimate 8 piece stack.

The next step was to turn my jagged 8 piece stack into a nice regular-shaped board I could work with.

I started by striking a reference line down the full length of the final glue-up 45 degrees relative to the base of the glue-up (For my purposes the base is the edge closest to the bottom right of the photo above.)

Using that reference I stuck another line parallel to it that just touched the bottom of the notches along the left edge. This didn't touch each notch-base exactly due to variances during the glue-up, but it was close enough to give me a point to work towards.

Because the protruding points of the original stacks didn't all line up perfectly due to those variances I just mentioned, I began to slowly nibble them away at the table saw by setting the fence about a half inch from the blade and guiding the tips as evenly as I could along it and through the blade. Each pass got me closer to where I needed to be, a nice straight cut, and after a few passes I had a pretty straight cut going down the edge. By checking against my reference lines I could see I was still on track for the 45 degree cut I was after.

I was then confident enough to move the fence over and take a larger cut along my outer reference line. Once that was done I turned the stack end for end, adjusted the fence, and cut the peaks off the other side in one pass. One more flip to trim a final sliver off the initial edge and I had a glued up stack with two clean, parallel edges to work with.

I was so excited at this point I screwed up and sliced a couple blanks that would ultimately be turned into dividers off the stack before I remembered I still needed to run it through the surface planer to true up the top and bottom. Fortunately I had made my glue-up much larger than actually needed so I didn't have to deal with the painful process of trying to even out those two initial blanks too. Small pieces are a pain to work with so I try to keep everything as large as possible as long as possible.

So anyway, all the calculating and measuring I did to ensure a stack as wide as possible but still able to fit through my planer was for naught, since now my stack was more than narrow enough to fit through the planer.

A couple of light passes on each side and my stack was finally nice a clean and straight all the way around.

Then it was back to the table saw to cut two more 7/16s blanks off the stack. I then cut those long blanks into shorter sections a little longer than the final pieces needed to be.

Two slices off the big stack was way more than needed for the jewelry box but the original Walnut and Maple boards were only about 3/4" thick and I felt that the rails needed to be slightly taller than that. To do that I was going to stack two pieces on top of each other then trim it down to the height I actually wanted. In order to keep the random width laminations lined up when I did this I needed to have the two pieces come from matching sections of the two adjacent blanks.

While I was handling the paired pieces I discovered that if I turned one of them 90 degrees and then glued them together in just the right alignment the resulting divider would be plenty high enough for what I wanted and it put a neat looking kink into the pattern, so I went with that instead of my original plan.

Since the strips were taller than wide this left a little excess overhang on one side that I trimmed off at the bandsaw, guiding the blade freehand down the edge of the vertical part of the assembly.

That narrow cutoff there on the right is what I ended up inlaying into the sides of the upper trays.

After trimming off the bottom to the height I wanted, I knocked the top corners of the dividers off with a hand plane.

Then a little sanding, by machine initially to rough out the shape then by hand down through the grits cleaned and polished the rails yet left each one slightly unique to avoid the whole mass-production look.

Here's an example of how my decision to turn one of the pieces 90 degrees before gluing resulted in two different looks. Standing up in the background of the photo above you can see the side that looks like it has a kink in it where each wood seems to bend around a 45 degree corner. Laying on their sides in the foreground are rails showing the other side where the pattern doesn't flow but appears interrupted. To my eye either way looks pretty interesting, more interesting that just a straight-line pattern.

So now all I needed to do was trim the rails to their final length, which I didn't do until just before installing them.